The End of Offshore Drilling in France

- 1. A new turn in the French policy

On February 20, 2020, the French government announced that it is definitely putting an end to offshore drilling in France (see the official announcement). As of April 2020, 17 research licenses and 63 exploitation licenses are still valid; 7 applications for an exploitation license have been introduced in metropolitan France. The number seems important but French oil production represents only 1% of its consumption, and the exploitation area covers 4000 km2 of the French territory as of May 2020 (see the last official report dated May 11, 2020).

The French political evolution in this regard is justified by its international commitments to the protection of the environment. It is indeed the transposition of the Paris Agreement, adopted on December 12, 2015 and ratified by France on October 5, 2016. This Agreement only sets up the objective for the States signatories to limit the increase in global average temperature below 2°C. The Agreement as such does not contain specific measures to be adopted by the States in relation to offshore exploitation. It is within their margin of appreciation to decide which measures to adopt in order to meet the mandatory goals established by the Agreement.

In France, the Paris Agreement is implemented first and foremost by the Climate Plan introduced in July 2016. Considering that the decrease of hydrocarbon exploitation by at least 80% would limit the increase of greenhouse gas emission, and therefore, maintain the objective of the Agreement, the Climate Plan aims to put an end to hydrocarbon exploitation.

This being said, the French government has recently announced in a press communication the extension of its continental shelf by more than 150.000 km2, after the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf has issued its recommendations on June 10, 2020. In line with its position on the environmental issue, the government has stated in this communication that the exploitation of these areas was not considered. On the contrary, such extension of the continental shelf would allow France to take measures in order to protect the marine environment of those areas.

The implementation of this political evolution regarding offshore drilling in French domestic law has been progressive. As soon as 2013, the government expressed its intent to reform the mining legislation in order to take into account environmental protection and the principles set out in the Charter for the Environment, namely workers’ safety and public safety. However, despite several attempts, the reform did not take place until a few years later with the adoption of the law n°2017-1839 of December 30, 2017. This legislation implements substantive changes in the regulation of offshore drilling in accordance with the International Law of the Sea framework, and particularly Article 81 of UNCLOS, which provides that “[t]he coastal State shall have the exclusive right to authorize and regulate drilling on the continental shelf for all purposes”.

The objective of this law is expressed in Article 2 which modifies Article L. 111-6 of the Mining Code and provides that it is gradually putting an end to the research and exploitation of carbon and all types of hydrocarbon, regardless of the techniques of extraction. The Mining Code distinguishes between two types of permits – research permits and exploitation permits – and attributes to them two different legal regimes.

- 2. The impact of the new drilling offshore policy on permits holders

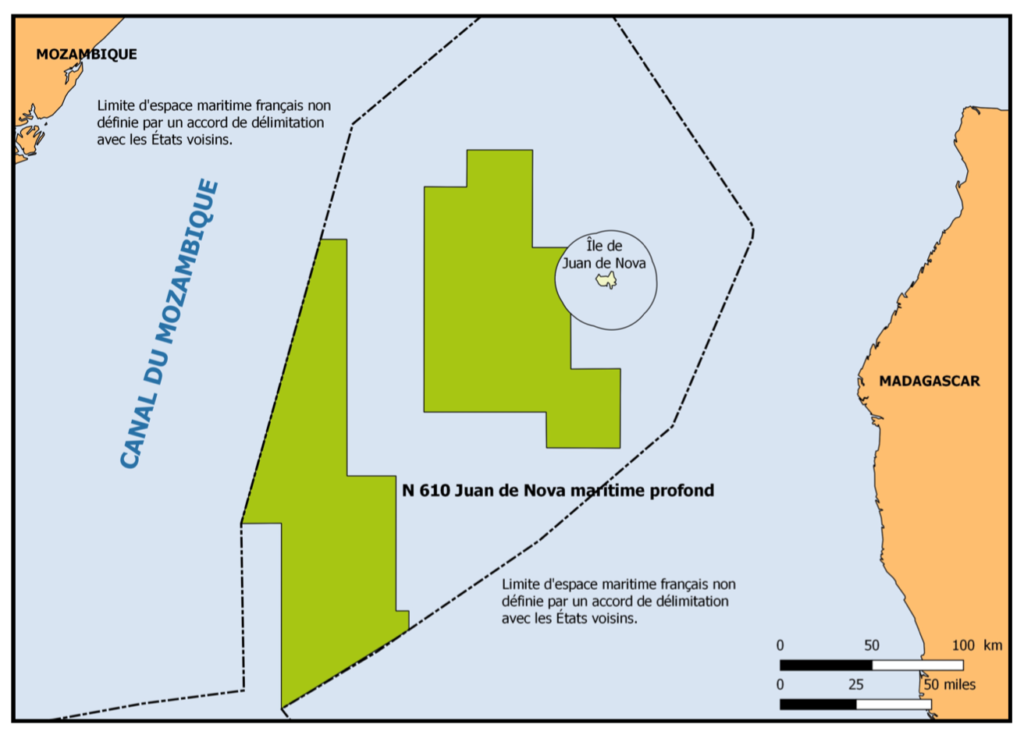

The main issue relating to these new measures is their impact on the industry and on the companies involved in offshore oil drilling. The last companies which had to face these measures are South Atlantic Petroleum, a Nigerian company, and Marex Petroleum, an American company. Both of them have been exploiting a research license known as “Juan de Nova Maritime Profond”. On February 20, 2020, the government announced its refusal to extend this license. The “Juan de Nova Maritime Profond” research license was initially granted to South Atlantic Petroleum and Rock Oil Company Ltd. in 2008. The latter was then substituted by Marex Petroleum in 2013, and in 2015, the license was extended until December 30, 2018. This project took place in the Exclusive Economic Zone declared by France around the Scattered Islands, a maritime zone in the Mozambique Channel which is disputed with Madagascar (see the recent analysis of the area by ZOMAD).

Map of the area covered by the « Juan de Nova Maritime Profond » research license. Source: https://www.ecologique-solidaire.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/2019_04.pdf

The “Juan de Nova Maritime Profond” license is the last offshore drilling research license outside of metropolitan France, after the “Guyane Maritime” project, which was terminated in June 2019 (see the April 2019 and April 2020 lists of the French mining titles).

The decision of the government follows the adoption of the 2017 legislation. Regarding concessions or exploitation permits, this legislation provides that the authority shall not grant any new concessions (Article L. 111-9, 2°). As regarding those permits’ extension, the same law provides that research licenses can only be extended up to January 1, 2040 (Article L. 111-9, 3°).

As for research permits which are of direct concern for the “Juan de Nova Maritime Profond” project, the law also states that new exclusive permits shall not be granted anymore by the competent authority (Article L. 111-9, 1°). However, according to this legislation, these permits can still be extended under Article 142-1 of the Mining Code which has not been modified in 2017. Article 142-1 indeed provides that:

“The validity of an exclusive research permit may be extended twice, each time for a maximum of five years, without new calls for competition.

The holder is entitled by law to benefit from each of these extensions, either for a period for at least three years, or for the same duration as the previous permit if the extension is shorter than three years. Such an extension is accorded when the holder has fulfilled his obligations and when a financial commitment at least equal to the one made for the previous period of validity, prorated to the validity period and the size of the area requested has been made.”[i]

However, the application for the extension of “Juan de Nova Maritime Profond” and the duration requested are not publicly available. Hence, it remains uncertain as whether South Atlantic Petroleum and Marex Petroleum could actually benefit from this provision.

This political turn regarding hydrocarbon exploitation is not implemented without difficulty from the point of view of the industries. This has been anticipated in the 2017 legislation, whose Article 7 states that the Government shall present to the Parliament a report introducing the measures to be taken to support the companies and their employees, within one year after the entry into force of the legislation. However, this report, which has not been made public, was only introduced on May 27, 2019. Article 7 specifies that one of the measures to be introduced is the “ecological and solidarity transition agreement” (contrat de transition écologique et solidaire) to be concluded between companies and the territories notably to plan the transition and the evolution of the industries within those territories. Besides those measures, it should be noted that, since this law is not retroactively applicable, it does not apply to license applications introduced before its entry into force, which remain valid until their expiration.

Only few refusals of permit issuances have been challenged by companies before the French domestic courts. Significantly, in June 2018, the French Conseil d’État rejected a claim by Esso and Total against a governmental decision refusing to issue a research permit (“Udo”) on hydrocarbon mines located on Guyana’s continental shelf. For the first time, the Conseil d’État considered global warming as an objective of general interest allowing for a limitation of the freedom of trade and industry and, by way of consequence, the refusal of a research license:

“[…] the long-standing question of the violation of the freedom of trade and industry by the contested provisions, which are moreover motivated by the general interest objective of limitation of global warming and by the necessity for France to respect its obligations under the Paris Climate Agreement, lacks substance.”[ii]

With this decision, the French higher administrative court has taken into account France’s international commitments regarding the protection of the environment.

The implications of this political evolution regarding offshore oil drilling are more complicated for the two companies involved in the “Juan de Nova Maritime Profond” permit, since the drilling was located in a disputed maritime area, which adds uncertainty for the investors, notably in the event of an arbitration claim and the choice of substantive law.

Léna Kim, Master’s degree (University of Angers). Trainee at Savoie Laporte

[i] Our translation. French original: “La validité d’un permis exclusif de recherches peut être prolongé à deux reprises, chaque fois de cinq ans au plus, sans nouvelle mise en concurrence. Chacune de ces prolongations est de droit, soit pour une durée au moins égale à trois ans, soit pour la durée de validité précédent si cette dernière est inférieure à trois ans, lorsque le titulaire a satisfait à ses obligations et souscrit dans la demande de prolongation un engagement financier au moins égal à l’engagement financier souscrit pour la période de validité précédente, au prorata de la validité et de la superficie sollicitées.”

[ii] Our translation. French original: “[…] la question de l’atteinte portée à la liberté du commerce et de l’industrie par les dispositions contestées, lesquelles sont au demeurant motivées par l’objectif d’intérêt général de limitation du réchauffement climatique et par la nécessité pour la France de respecter ses engagements pris au titre de l’Accord de Paris sur le climat, qui n’est pas nouvelle, ne présente pas un caractère sérieux. ”.